micro::bit v2 Embedded Discovery Book

Discover the world of microcontrollers through Rust!

This book is an introductory course on microcontroller-based embedded systems that uses Rust as the teaching language rather than the usual C/C++.

Scope

The following topics will be covered (eventually, I hope):

-

How to write, build, flash and debug an “embedded” (Rust) program.

-

Functionality (“peripherals”) commonly found in microcontrollers: Digital input and output, Pulse Width Modulation (PWM), Analog to Digital Converters (ADC), common communication protocols like Serial, I2C and SPI, etc.

-

Multitasking concepts: cooperative vs preemptive multitasking, interrupts, schedulers, etc.

-

Control systems concepts: sensors, calibration, digital filters, actuators, open loop control, closed loop control, etc.

Approach

-

Beginner friendly. No previous experience with microcontrollers or embedded systems is required.

-

Hands on. Plenty of exercises to put the theory into practice. You will be doing most of the work here.

-

Tool centered. We’ll make plenty use of tooling to ease development. “Real” debugging, with GDB, and logging will be introduced early on. Using LEDs as a debugging mechanism has no place here.

Non-goals

What’s out of scope for this book:

-

Teaching Rust. There’s plenty of material on that topic already. We’ll focus on microcontrollers and embedded systems.

-

Being a comprehensive text about electric circuit theory or electronics. We’ll just cover the minimum required to understand how some devices work.

-

Covering details such as linker scripts and the boot process. For example, we’ll use existing tools to help get your code onto your board, but not go into detail about how those tools work.

Also I don’t intend to port this material to other development boards; this book will make exclusive use of the micro:bit development board.

Reporting problems

The source of this book is in this repository. If you encounter any typo or problem with the code report it on the issue tracker.

Other embedded Rust resources

This Discovery book is just one of several embedded Rust resources provided by the Embedded Working Group. The full selection can be found at The Embedded Rust Bookshelf. This includes the list of Frequently Asked Questions.

Background

You are about to write “bare-metal” Rust for a microcontroller. Maybe you have never done anything like this before. That’s fantastic — welcome to an awesome adventure!

We should start by answering some basic questions you might have.

-

What’s a microcontroller?

A microcontroller is a system on a chip. Whereas your computer is made up of several discrete components: a processor, RAM, storage, an Ethernet port, etc.; a microcontroller has all those types of components built into a single “chip” or package. This makes it possible to build systems with fewer parts.

-

What can you do with a microcontroller?

Lots of things! Microcontrollers are the central part of what are known as “embedded systems”. Embedded systems are everywhere, but you don’t usually notice them. They control the machines that wash your clothes, print your documents, and cook your food. Embedded systems keep the buildings that you live and work in at a comfortable temperature, and control the components that make the vehicles you travel in stop and go.

Most embedded systems operate without user intervention. Even if they expose a user interface like a washing machine does; most of their operation is done on their own.

Embedded systems are often used to control a physical process. To make this possible, they have one or more devices to tell them about the state of the world (“sensors”), and one or more devices which allow them to change things (“actuators”). For example, a building climate control system might have:

- Sensors which measure temperature and humidity in various locations.

- Actuators which control the speed of fans.

- Actuators which cause heat to be added or removed from the building.

-

When should I use a microcontroller?

Many of the embedded systems listed above could be implemented with a computer running Linux (for example a “Raspberry Pi”). Why use a microcontroller instead? Sounds like it might be harder to develop a program.

Some reasons might include:

-

Cost: A microcontroller is much cheaper than a general purpose computer. Not only is the microcontroller cheaper; it also requires many fewer external electrical components to operate. This makes Printed Circuit Boards (PCB) smaller and cheaper to design and manufacture.

-

Power consumption: Most microcontrollers consume a fraction of the power of a full blown processor. For applications which run on batteries, that makes a huge difference.

-

Responsiveness: To accomplish their purpose, some embedded systems must always react within a limited time interval (e.g. the “anti-lock” braking system of a car). If the system misses this type of deadline, a catastrophic failure might occur. Such a deadline is called a “hard real time” requirement. An embedded system which is bound by such a deadline is referred to as a “hard real-time system”. A general purpose computer and OS usually has many software components which share the computer’s processing resources. This makes it harder to guarantee execution of a program within tight time constraints.

-

Reliability. In systems with fewer components (both hardware and software), there is less to go wrong!

-

-

When should I not use a microcontroller?

Microcontrollers are often not great at heavy computational work. To keep their cost and power consumption low, microcontrollers have limited computational resources available to them.

Microcontrollers can typically execute fewer instructions per second than “big” processors. The slowest parts might run at “only” a few million instructions per second. In addition, the amount of work per instruction is typically lower. Microcontroller parts are typically “32 bit”, but “16 bit” parts are not uncommon: this may mean more instructions to work with typical Rust datatypes. Most microcontrollers have no or little “cache”, meaning instructions can run only as fast as main memory can be accessed.

Some microcontrollers don’t have hardware support for floating point operations. On those devices, performing a simple addition of single precision numbers can take hundreds of CPU cycles.

Finally, microcontrollers typically come with limited memory. Memory sizes may be as small as 16KB for program instructions and 4KB for data, making programming for these systems quite challenging. While the internal memory size per unit cost and power consumption is constantly increasing, the processor we will work with still has “only” 512KB for program instructions and 256KB for data — far less than that of a “real computer”.

-

Why use Rust and not C?

Hopefully, I don’t need to convince you here as you are probably familiar with the language differences between Rust and C. One point I do want to bring up is package management. C lacks an official, widely accepted package management solution whereas Rust has Cargo. This makes development much easier. And, IMO, easy package management encourages code reuse because libraries can be easily integrated into an application which is also a good thing as libraries get more “battle testing”.

-

Why should I not use Rust?

Or why should I prefer C over Rust?

The C ecosystem is more mature. Off-the-shelf solutions for several problems already exist. If you need to control a time sensitive process, you can grab one of the existing commercial Real Time Operating Systems (RTOS) out there and solve your problem. There are no commercial, production-grade RTOSes in Rust (as of this writing) so you would have to either create one yourself or try one of the ones that are in development. You can find a list of those in the Awesome Embedded Rust repository.

Hardware/knowledge requirements

The primary knowledge requirement to read this book is to know some Rust. It’s hard for me to quantify some. Being familiar with the basics of generics and traits is quite helpful. You do need to know how to use closures. You also need to be familiar with the idioms of the current Rust edition.

Also, to follow this material you’ll need:

-

A Micro:Bit v2 (MB2) board.

You can purchase this board from many suppliers, including Amazon and Ali Baba. You can get a list of suppliers directly from the BBC, the manufacturers of MB2.

There are several versions of the

V2board available. While the material here was written forV2.00, things should work fine with with anyV2board. -

A micro-B USB cable (nothing special — you probably have many of these). This is required to power the micro:bit board when not on battery, and to communicate with it. Make sure that the cable supports data transfer, as some cables only support charging devices.

NOTE Some micro:bit kits ship with such cables. USB cables used with other mobile devices should work, if they are micro-B and have the capability to transmit data.

The official

micro:bit Gokit provides both the USB cable and a nifty battery pack for powering the MB2 without USB.

FAQ: Wait, why do I need this specific hardware?

It makes my life and yours much easier.

The material is much, much more approachable if we don’t have to worry about hardware differences. Trust me on this one.

FAQ: Can I follow this material with a different development board?

Maybe? It depends mainly on two things: your previous experience with microcontrollers and/or

whether a high level crate already exists for your development board somewhere. You probably want at

least a HAL crate, like nrf52833-hal used here. You may prefer a board with a Board Support crate,

like microbit-v2 used here. If you intend to use a different microcontroller, you can look

through Awesome Embedded Rust or just search the web to find supported crates.

With a different development board, this text loses most if not all its beginner friendliness and “easy to follow”-ness, in my opinion: you have been warned.

If you have a different Arm-based development board and you don’t consider yourself a total beginner, you might consider starting with the quickstart project template.

Setting up a development environment

Dealing with microcontrollers involves several tools as we’ll be dealing with an architecture different from your computer’s and we’ll have to run and debug programs on a “remote” device.

Documentation

Tooling is not everything though. Without documentation, it is pretty much impossible to work with microcontrollers. The official MB2 technical documentation is at https://tech.microbit.org. We will reference other technical documentation throughout the book.

Tools

We’ll use all the tools listed below. Where a minimum version is not specified, any recent version should work but we have listed the version we have tested.

-

Rust 1.79.0 or a newer toolchain.

-

gdb-multiarch. This is a debugging tool. The oldest tested version is 10.2, but other versions will most likely work as well. If your distribution/platform does not havegdb-multiarchavailablearm-none-eabi-gdbwill do the trick as well. Furthermore, some normalgdbbinaries are built with multiarch capabilities as well: you can find further information about this in the debugging chapter of this book. -

cargo-binutils. Version 0.3.6 or newer. -

probe-rs-tools. Version 0.24.0 or newer. -

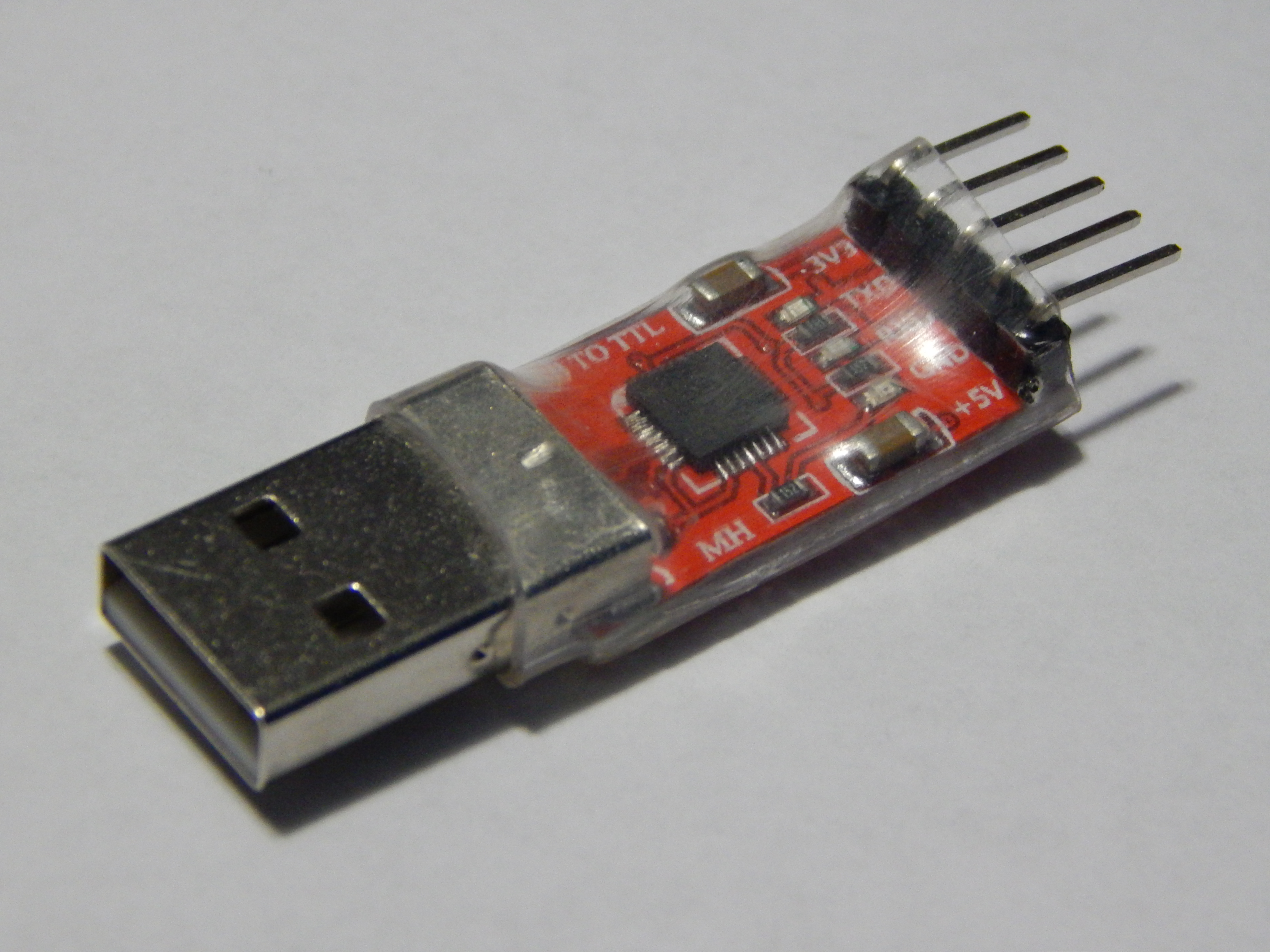

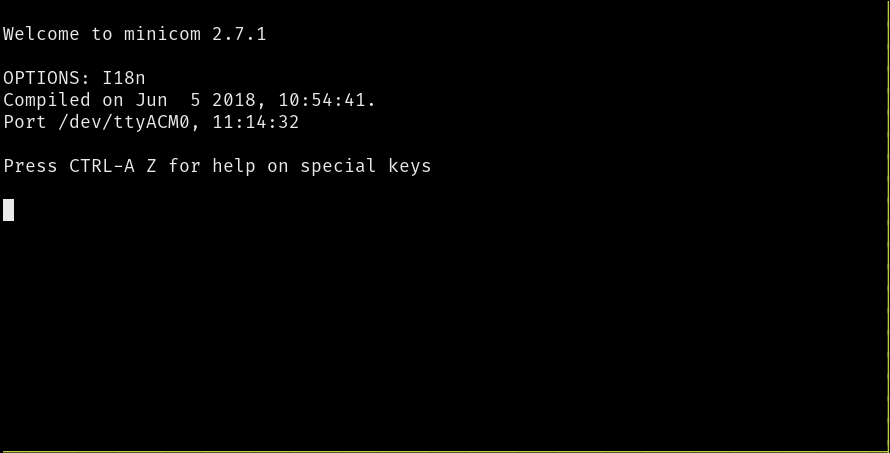

minicomon Linux and macOS. Tested version: 2.7.1. Other versions will most likely work as well though. -

PuTTYon Windows.

Next, follow OS-agnostic installation instructions for a few of the tools:

rustc & Cargo

Install rustup by following the instructions at https://rustup.rs.

If you already have rustup installed, double check that you are on the stable channel and your

stable toolchain is up-to-date. rustc -V should return a date and version no older than the one

shown below:

$ rustc -V

rustc 1.79.0 (129f3b996 2024-06-10)

cargo-binutils

$ rustup component add llvm-tools

$ cargo install cargo-binutils --vers '^0.3'

$ cargo size --version

cargo-size 0.3.6

probe-rs-tools

NOTE If you already have old versions of probe-run, probe-rs or cargo-embed installed

on your system, remove them before starting this step, as they could conceivably cause problems

for you down the line. In particular, probe-run no longer officially exists. Try these as

needed:

$ cargo uninstall cargo-embed

$ cargo uninstall probe-run

$ cargo uninstall probe-rs

$ cargo uninstall probe-rs-cli

In order to install probe-rs-tools, go to https://probe.rs and follow the current installation

instructions there.

-

NOTE If you prefer to install

probe-rs-toolsusingcargo install, you can try the following steps. Folks have experienced frequent failures with this approach, but you are welcome to give it a go.-

Upgrade to the most recent stable Rust.

-

Install the

probe-rs-toolsbinary prerequisites. (The linked instructions are part of the more generalprobe-rsembedded debugging toolkit documentation.) -

Try the install

$ cargo install --locked probe-rs-tools

-

Installing probe-rs-tools will install several useful tools, including probe-rs and

cargo-embed (which is normally run as a Cargo command). Check that things are working before

proceeding.

$ cargo embed --version

cargo-embed 0.24.0 (git commit: crates.io)

This repository

This book also contains some small Rust codebases used in various chapters: the easiest way to use these is to download the book’s source code. You can do this in one of the following ways:

-

Visit the repository, click the green “Code” button and then the “Download Zip” one.

-

Clone it using

git(if you knowgityou presumably already have it installed) from the same repository as linked in the Zip approach.

OS specific instructions

Now follow the instructions specific to the OS you are using:

Linux

Here are the installation commands for a few Linux distributions.

Ubuntu 20.04 or newer / Debian 10 or newer

NOTE

gdb-multiarchis the GDB command you’ll use to debug your Arm Cortex-M programs.

$ sudo apt install gdb-multiarch minicom libunwind-dev

Fedora 32 or newer

NOTE

gdbis the GDB command you’ll use to debug your Arm Cortex-M programs.

$ sudo dnf install gdb minicom libunwind-devel

Arch Linux

NOTE

gdbis the GDB command you’ll use to debug your Arm Cortex-M programs.

$ sudo pacman -S arm-none-eabi-gdb minicom libunwind

Other distros

NOTE

arm-none-eabi-gdbis the GDB command you’ll use to debug your Arm Cortex-M programs.

For distros that don’t have packages for Arm’s pre-built

toolchain, download the “Linux

64-bit” file and put its bin directory on your path. Here’s one way to do it:

$ mkdir -p ~/local

$ cd ~/local

$ tar xjf /path/to/downloaded/XXX.tar.bz2

Then, use your editor of choice to append to your PATH in the appropriate shell init file

(e.g. ~/.zshrc or ~/.bashrc):

PATH=$PATH:$HOME/local/XXX/bin

udev rules

These rules let you use USB devices like the micro:bit without root privilege, i.e. sudo.

Create this file in /etc/udev/rules.d with the content shown below.

$ cat /etc/udev/rules.d/69-microbit.rules

# CMSIS-DAP for microbit

ACTION!="add|change", GOTO="microbit_rules_end"

SUBSYSTEM=="usb", ATTR{idVendor}=="0d28", ATTR{idProduct}=="0204", TAG+="uaccess"

LABEL="microbit_rules_end"

Then reload the udev rules with:

$ sudo udevadm control --reload

If you had any board plugged to your computer, unplug them and then plug them in again, or run the following command.

$ sudo udevadm trigger

Verify permissions

Connect the micro:bit to your computer using a USB cable.

The micro:bit should now appear as a USB device (file) in /dev/bus/usb. Let’s find out how it got

enumerated:

$ lsusb | grep -i "NXP Arm mbed"

Bus 001 Device 065: ID 0d28:0204 NXP Arm mbed

$ # ^^^ ^^^

In my case, the micro:bit got connected to the bus #1 and got enumerated as the device #65. This means the

file /dev/bus/usb/001/065 is the micro:bit. Let’s check the file permissions:

$ ls -l /dev/bus/usb/001/065

crw-rw-r--+ 1 nobody nobody 189, 64 Sep 5 14:27 /dev/bus/usb/001/065

The permissions should be crw-rw-r--+, note the + at the end, then see your access rights by running the following command.

$ getfacl /dev/bus/usb/001/065

getfacl: Removing leadin '/' from absolute path names

# file: dev/bus/usb/001/065

# owner: nobody

# group: nobody

user::rw-

user:<YOUR-USER-NAME>:rw-

group::rw-

mask::rw-

other::r-

You should see your username in the list above with the

rw- permissions, if not … then check your udev rules

and try re-loading them with:

$ sudo udevadm control --reload

$ sudo udevadm trigger

Now, go to the next section.

Windows

arm-none-eabi-gdb

Arm provides .exe installers for Windows. Grab one from here, and follow the instructions.

Just before the installation process finishes tick/select the “Add path to environment variable”

option. Then verify that the tools are in your %PATH%:

$ arm-none-eabi-gcc -v

(..)

gcc version 5.4.1 20160919 (release) (..)

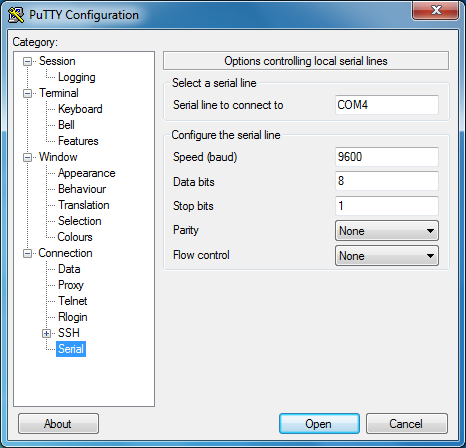

PuTTY

Download the latest putty.exe from this site and place it somewhere in your %PATH%.

Now, go to the next section.

macOS

All the tools can be installed using Homebrew:

$ # GDB debugger - The version in brew is built for all architectures including all of the ARM embedded cores

$ brew install gdb

$ # Minicom

$ brew install minicom

$ # lsusb lists USB ports

$ brew install lsusb

That’s all! Go to the next section.

Verify the installation

Let’s verify that all the tools were installed correctly.

Verifying cargo-embed

First, connect the micro:bit to your Computer using a USB cable.

At least an orange LED right next to the USB port of the micro:bit should light up. Furthermore, if you have never flashed another program on to your micro:bit, the default program the micro:bit ships with should start blinking the red LEDs on its back: you can ignore them, or you can play with the demo app.

Now let’s see if probe-rs, and by extensions cargo-embed can see your micro:bit. You can do this by running the following command:

$ probe-rs list

The following debug probes were found:

[0]: BBC micro:bit CMSIS-DAP -- 0d28:0204:990636020005282030f57fa14252d446000000006e052820 (CMSIS-DAP)

Or if you want more information about the micro:bits debug capabilities then you can run:

$ probe-rs info

Probing target via JTAG

Error identifying target using protocol JTAG: The probe does not support the JTAG protocol.

Probing target via SWD

Arm Chip with debug port Default:

Debug Port: DPv1, DP Designer: Arm Ltd

├── 0 MemoryAP

│ └── ROM Table (Class 1), Designer: Nordic VLSI ASA

│ ├── Cortex-M4 SCS (Generic IP component)

│ │ └── CPUID

│ │ ├── IMPLEMENTER: Arm Ltd

│ │ ├── VARIANT: 0

│ │ ├── PARTNO: Cortex-M4

│ │ └── REVISION: 1

│ ├── Cortex-M3 DWT (Generic IP component)

│ ├── Cortex-M3 FBP (Generic IP component)

│ ├── Cortex-M3 ITM (Generic IP component)

│ ├── Cortex-M4 TPIU (Coresight Component)

│ └── Cortex-M4 ETM (Coresight Component)

└── 1 Unknown AP (Designer: Nordic VLSI ASA, Class: Undefined, Type: 0x0, Variant: 0x0, Revision: 0x0)

Debugging RISC-V targets over SWD is not supported. For these targets, JTAG is the only supported protocol. RISC-V specific information cannot be printed.

Debugging Xtensa targets over SWD is not supported. For these targets, JTAG is the only supported protocol. Xtensa specific information cannot be printed.

Next, make sure you are in src/03-setup of this book’s source code. Then run these commands:

$ rustup target add thumbv7em-none-eabihf

$ cargo embed --target thumbv7em-none-eabihf

If everything works correctly cargo-embed should first compile the small example program in this directory, then flash it and finally open a nice text based user interface that prints Hello World.

(If it does not, check out general troubleshooting instructions.)

This output is coming from the small Rust program you just flashed on to your micro:bit. Everything is working properly and you can continue with the next chapters!

Getting the most out of your IDE

All code in this book assumes that you use a simple terminal to build your code, run it, and interact with it. It also makes no assumption about your text editor.

However, you may have your favourite IDEs, providing you auto-complete, type annotation, your preferred shortcuts and much more. This section explains how to get the most out of your IDE using the code obtained from this book’s repo.

IDE configuration

Below, we explain how to configure your IDE to get the most out of this book. If your IDE is not listed below, please improve this book by adding a section, so that the next reader can get the best experience out of it.

How to build with IntelliJ

When editing the IntelliJ build configuration, here are a few non-default values:

- You should edit the command. When this book tells you to run

cargo embed FLAGS, You’ll need to replace the default valuerunby the commandembed FLAGS, - You should enable “Emulate terminal in output console”. Otherwise, your program will fail to print text to a terminal

- You should ensure that the working directory is

microbit/src/N-name, withN-namebeing the directory of the chapter you are reading. You can not run from thesrcdirectory since it contains no cargo file.

Meet your hardware

Let’s get familiar with the hardware we’ll be working with.

micro:bit

Here are some of the many components on the board:

- A microcontroller.

- A number of LEDs, most notably the LED matrix on the back

- Two user buttons as well as a reset button (the one next to the USB port).

- One USB port.

- A sensor that is both a magnetometer and an accelerometer

Of these components, the most important is the microcontroller (sometimes shortened to “MCU” for “microcontroller unit”), which is the bigger of the two black squares sitting on the side of the board with the USB port. The MCU is what runs your code. You might sometimes read about “programming a board”, when in reality what we are doing is programming the MCU that is installed on the board.

If you happen to be interested in a more detailed description of the board you can checkout the micro:bit website.

Since the MCU is so important, let’s take a closer look at the one sitting on our board.

Nordic nRF52833 (the “nRF52”, micro:bit v2)

Our MCU has 73 tiny metal pins sitting right underneath it (it’s a so called aQFN73 chip). These pins are connected to traces, the little “roads” that act as the wires connecting components together on the board. The MCU can dynamically alter the electrical properties of the pins. This works similarly to a light switch, altering how electrical current flows through a circuit. By enabling or disabling electrical current to flow through a specific pin, an LED attached to that pin (via the traces) can be turned on and off.

Each manufacturer uses a different part numbering scheme, but many will allow you to

determine information about a component simply by looking at the part number. Looking at our

MCU’s part number we find N52833 QIAAA0 2024AL: you probably cannot see it with your bare

eye, but it is on the chip. (If you have a later revision of MB2, your number may vary

somewhat. This not an issue. The N52833 part should be there, though.) The N at the

front hints to us that this is a part manufactured by Nordic Semiconductor. Looking up

the part number on their website we quickly find the product page. There we learn that

our chip’s main marketing point is that it is a “Bluetooth Low Energy and 2.4 GHz SoC” (SoC

being short for “System on a Chip”), which explains the RF in the product name since RF is

short for radio frequency. If we search through the documentation of the chip linked on the

product page for a bit we find the product specification which contains chapter 10

“Ordering Information” dedicated to explaining the weird chip naming. Here we learn that:

- The

N52is the MCU’s series, indicating that there are othernRF52MCUs - The

833is the part code - The

QIis the package code, short foraQFN73 - The

AAis the variant code, indicating how much RAM and flash memory the MCU has, in our case 512 kilobyte flash and 128 kilobyte RAM - The

A0is the build code, indicating the hardware version (A) as well as the product configuration (0) - The

2024ALis a tracking code, hence it might differ on your chip

The product specification does of course contain a lot more useful information about the chip: for example, that the chip is an Arm® Cortex™-M4 32-bit processor.

Arm? Cortex-M4?

If our chip is manufactured by Nordic, then who is Arm? And if our chip is the nRF52833, what is the Cortex-M4?

You might be surprised to hear that while “Arm-based” chips are quite popular, the company behind the “Arm” trademark (Arm Holdings) doesn’t actually manufacture chips for purchase. Instead, their primary business model is to just design parts of chips. They will then license those designs to manufacturers, who will in turn implement the designs (perhaps with some of their own tweaks) in the form of physical hardware that can then be sold. Arm’s strategy here is different from companies like Intel, which both designs and manufactures their chips.

Arm licenses a bunch of different designs. Their “Cortex-M” family of designs are mainly used as the core in microcontrollers. For example, the Cortex-M4 (the core our chip is based on) is designed for low cost and low power usage. The Cortex-M7 is higher cost, but with more features and performance.

Luckily, you don’t need to know too much about different types of processors or Cortex designs for the sake of this book. However, you are hopefully now a bit more knowledgeable about the terminology of your device. While you are working specifically with an nRF52833, you might find yourself reading documentation and using tools for Cortex-M-based chips, as the nRF52833 is based on a Cortex-M design.

Rust Embedded terminology

Before we dive into programming the micro:bit let’s have a quick look at the libraries and terminology that will be important for all the future chapters.

Abstraction layers

For any fully supported microcontroller/board with a microcontroller, you will usually hear the following terms being used for their levels of abstraction:

Peripheral Access Crate (PAC)

The job of the PAC is to provide a safe (ish) direct interface to the peripherals of the chip, allowing you to configure every last bit however you want (of course also in wrong ways). Usually you only ever have to deal with the PAC if either the layers that are higher up don’t fulfill your needs or when you are developing higher-level code for them. Unsurprisingly, the PAC we are (mostly implicitly) going to use is for the nRF52.

Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL)

The job of the HAL is to build up on top of the chip’s PAC and provide an abstraction that is actually usable for someone who does not know about all the special behaviour of this chip. Usually a HAL abstracts whole peripherals away into single structs that can, for example, be used to send data around via the peripheral. We are going to use the nRF52-hal.

Board Support Crate (BSP)

(In non-Rust situations this is usually called the Board Support Package, hence the acronym.)

The job of the BSP is to abstract a whole board (such as the micro:bit) away at once. That means it

has to provide abstractions to use both the microcontroller as well as the sensors, LEDs etc. that

might be present on the board. Quite often (especially with custom-made boards) no pre-built BSP

will be available. Instead you will be working with a HAL for the chip and build the drivers for the

sensors either yourself or search for them on crates.io. Luckily for us though, the micro:bit does

have a BSP, so we are going to use that on top of our HAL as well.

Unifying the layers

Next we are going to have a look at a very central piece of software

in the Rust Embedded world: embedded-hal. As its name suggests it

relates to the 2nd level of abstraction we got to know: the HALs.

The idea behind embedded-hal is to provide a set of traits that

describe behaviour which is usually shared across all implementations

of a specific peripheral in all the HALs. For example one would always

expect to have functions that are capable of turning the power on a pin

either on or off: to switch an LED on and off on the board or whatever.

embedded-hal allows us to write a driver for some piece of hardware, for example a temperature

sensor, that can be used on any chip for which an implementation of the embedded-hal traits

exists. This is accomplished by writing the driver in such a way that it only relies on the

embedded-hal traits. Drivers that are written in such a way are called platform-agnostic.

Luckily for us, the drivers we will be getting from crates.io are almost all platform agnostic.

Further reading

If you want to learn more about these levels of abstraction, Franz Skarman (a.k.a. TheZoq2) held a talk about this topic during Oxidize 2020: An Overview of the Embedded Rust Ecosystem.

Meet your software

In this chapter we will learn how to build, run and debug some very simple programs. The goal here is not to get into the details of MB2 Rust programming (yet), but to just familiarize yourself with the mechanics of the process.

First, a quick note about the conventions used in the rest of this book. We expect you to get a copy of the whole book with

git clone http://github.com/rust-embedded/discovery-mb2

The book’s “source code” is in discovery-mb2/mdbook/src. You should go there in your copy and look

around a bit. Each chapter directory has both the source Markdown text and the complete source for

all the programs in that chapter. When we refer to some path like src/main.rs, we mean that place

starting from the chapter you are working in. For example, your discovery-mb2 has a file called

mdbook/src/05-meet-your-software/examples/init.rs. We will refer to that file as just

examples/init.rs in this chapter.

There are two basic kinds of Rust code: “binary” executable programs, and “library” code. The library code won’t play a huge role in this book. Binary program source code can live in one of several places:

-

A program in

src/main.rswill be automatically compiled and run bycargo embedorcargo run. No special flags are needed. -

A program in

examples/foo.rscan be compiled and run bycargo embed --example fooorcargo run --example foo. -

A program in

src/bin/bar.rscan be compiled and run bycargo embed --bin barorcargo run --bin bar.

This is confusing, but it’s a standard convention of Cargo.

Now let’s move on and work with all this.

Embedded Setup

Let’s take a look at our first program to compile. Check the examples/init.rs file:

#![deny(unsafe_code)]

#![no_main]

#![no_std]

use cortex_m::asm;

use cortex_m_rt::entry;

use microbit as _;

use panic_halt as _;

#[entry]

fn main() -> ! {

#[allow(clippy::needless_late_init)]

let _y;

let x = 42;

_y = x;

// infinite loop; just so we don't leave this stack frame

loop {

asm::nop();

}

}Microcontroller programs are different from standard programs in two aspects: #![no_std] and

#![no_main].

The no_std attribute says that this program won’t use the std crate, which assumes an underlying

OS; the program will instead use the core crate, a subset of std that can run on bare metal

systems (that is, systems without OS abstractions like files and sockets).

The no_main attribute says that this program won’t use the standard main interface, which is

tailored for command line applications that receive arguments. Instead of the standard main we’ll

use the entry attribute from the cortex-m-rt crate to define a custom entry point. In this

program we have named the entry point main, but any other name could have been used. The entry

point function must have signature fn() -> !; this type indicates that the function can’t return.

This means that the program never terminates by returning from main: if the compiler detects that

this would be possible it will refuse to compile your program.

If you are a careful observer, you’ll also notice there is a possibly-hidden .cargo directory in

the Cargo project as well. This directory contains a Cargo configuration file .cargo/config.toml.

[build]

target = "thumbv7em-none-eabihf"

[target.thumbv7em-none-eabihf]

runner = "probe-rs run --chip nRF52833_xxAA"

rustflags = [

"-C", "linker=rust-lld",

]

This file tweaks the linking process to tailor the memory layout of the program to the requirements

of the target device. This modified linking process is a requirement of the cortex-m-rt

crate. The .cargo/config.toml file also tells Cargo how to build and run code on our MB2.

There is also an Embed.toml file here:

[default.general]

chip = "nrf52833_xxAA"

[default.reset]

halt_afterwards = true

[default.rtt]

enabled = false

[default.gdb]

enabled = true

This file tells cargo-embed that:

- We are working with an NRF52833.

- We want to halt the chip after flashing it, so our program stops before

main. - We want to disable RTT. RTT is a protocol that allows the chip to send text to a debugger. You have already seen RTT in action: it was the protocol that sent “Hello World” in chapter 3.

- We want to enable GDB. This will be required for the debugging procedure.

Now that we’ve seen what’s going on, let’s start by building this program.

Build it

The first step is to build our “binary” crate. Because the microcontroller has a different

architecture than your computer we’ll have to cross compile. Cross compiling in Rust land is as

simple as passing an extra --target flag to rustcor Cargo. The complicated part is figuring out

the argument of that flag: the name of the target.

As we already know the microcontroller on the micro:bit v2 has a Cortex-M4F processor in it.

rustc knows how to cross-compile to the Cortex-M architecture and provides several different

targets that cover the different processors families within that architecture:

thumbv6m-none-eabi, for the Cortex-M0 and Cortex-M1 processorsthumbv7m-none-eabi, for the Cortex-M3 processorthumbv7em-none-eabi, for the Cortex-M4 and Cortex-M7 processorsthumbv7em-none-eabihf, for the Cortex-M4F and Cortex-M7F processorsthumbv8m.main-none-eabi, for the Cortex-M33 and Cortex-M35P processorsthumbv8m.main-none-eabihf, for the Cortex-M33F and Cortex-M35PF processors

“Thumb” here refers to a version of the Arm instruction set that has smaller instructions for

reduced code size (it’s a pun, see). The hf/F parts have hardware floating point

acceleration. This will make numeric computations involving fractional (“floating decimal point”)

computations much faster.

For the micro:bit v2, we’ll want the thumbv7em-none-eabihf target.

Before cross-compiling you have to download a pre-compiled version of the standard library (a

reduced version of it, actually) for your target. That’s done using rustup:

$ rustup target add thumbv7em-none-eabihf

You only need to do the above step once; rustup will then update this target (re-installing a new

standard library rust-std component that contains the core library we use) whenever you update

your toolchain. Therefore you can skip this step if you have already added the necessary target

while verifying your setup.

With the rust-std component in place you can now cross compile the program using Cargo. Make sure

you are in the mdbook/src/05-meet-your-software directory in the Git repo, then build. This initial code

is an example, so we compile it as such.

$ cargo build --example init

Compiling semver-parser v0.7.0

Compiling proc-macro2 v1.0.86

...

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 33.67s

NOTE Be sure to compile this crate without optimizations. The provided

Cargo.tomlfile and build command above will ensure optimizations are off as long as you don’t passcargothe--releaseflag.

OK, now we have produced an executable. This executable won’t blink any LEDs: it’s just a simplified version that we will build upon later in the chapter. As a sanity check, let’s verify that the produced executable is actually an Arm binary. (The command below is equivalent to

readelf -h ../../../target/thumbv7em-none-eabihf/debug/examples/init

on systems that have readelf.)

$ cargo readobj --example init -- --file-headers

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.01s

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 01 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF32

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX - System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: EXEC (Executable file)

Machine: Arm

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0x117

Start of program headers: 52 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 793112 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x5000400

Size of this header: 52 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 32 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 4

Size of section headers: 40 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 21

Section header string table index: 19

If your numbers don’t exactly match these, don’t worry: a lot of this is quite dependent on the current build environment.

Next, we’ll flash the program into our microcontroller.

Flash it

Flashing is the process of moving our program into the microcontroller’s persistent memory. Once flashed, the microcontroller will execute the flashed program every time it is powered on.

Our program will be the only program in the microcontroller memory. By this I mean that there’s nothing else running on the microcontroller: no OS, no “daemon”, nothing. Our program has full control over the device.

Flashing the binary itself is quite simple, thanks to cargo embed.

Before executing that command though, let’s look into what it actually does. If you look at the side of your micro:bit with the USB connector facing upwards, you will notice that there are actually three black squares on there. The biggest one is a speaker. Another is our MCU we already talked about… but what purpose does the remaining one serve? This chip is another MCU, an NRF52820 almost as powerful as the NRF52833 we will be programming! This chip has three main purposes:

- Enable power and reset control of our NRF52833 MCU from the USB connector.

- Provide a serial to USB bridge for our MCU.

- Provide an interface for programming and debugging our NRF52833 (this is the relevant purpose for now).

This chip acts as sort of bridge between our computer (to which it is connected via USB) and the MCU (to which it is connected via traces and communicates with using the SWD protocol). This bridge enables us to flash new binaries on to the MCU, inspect a program’s state via a debugger and do other useful things.

So lets flash it!

$ cargo embed --example init

(...)

Erasing sectors ✔ [00:00:00] [####################################################################################################################################################] 2.00KiB/ 2.00KiB @ 4.21KiB/s (eta 0s )

Programming pages ✔ [00:00:00] [####################################################################################################################################################] 2.00KiB/ 2.00KiB @ 2.71KiB/s (eta 0s )

Finished flashing in 0.608s

You will notice that cargo-embed does not exit after outputting the last line. This is intended:

you should not close cargo-embed, since we need it in this state for the next step — debugging it!

Furthermore, you will have noticed that cargo build and cargo embed are actually passed the same

flags. This is because cargo embed actually executes the build and then flashes the resulting

binary on to the chip. This means you can leave out the cargo build step in the future if you want

to flash your code right away.

Debug it

Let’s figure out how to debug our little program. It doesn’t really have any interesting bugs yet, but that’s the best kind of program to learn debugging on.

How does this even work?

Before we debug our program let’s take a moment to quickly understand what is actually happening here. In the previous chapter we already discussed the purpose of the second chip on the board, as well as how it talks to our computer, but how can we actually use it?

The little option default.gdb.enabled = true in Embed.toml made cargo embed open a so-called

“GDB stub” after flashing. This is a server that our GDB can connect to and send commands like “set

a breakpoint at address X”. The server can then decide on its own how to handle this command. In the

case of the cargo embed GDB stub it will forward the command via USB to the “debugging probe” on

the second chip. This chip does the job of talking to the MCU for us.

Let’s debug!

cargo-embed is running in our current shell. We can open a new shell and go back into our project

directory. Once we are there we first have to open the binary in gdb like this:

$ gdb ../../../target/thumbv7em-none-eabihf/debug/examples/init

NOTE Depending on which GDB you installed you will have to use a different command to launch it. Check out chapter 3 if you forgot which one it was.

The ../../.. in this command is needed, since each example project is in a “workspace” that

contains the entire book. Workspaces have a single shared target directory. Check out Workspaces

chapter in Rust Book for more.

NOTE If

cargo-embedprints a lot of warnings here don’t worry about it. As of now it does not fully implement the GDB protocol, and thus might not recognize all the commands your GDB is sending to it. As long as GDB does not crash, you are fine.

Next we will have to connect to the GDB stub. It runs on localhost:1337 by default so in order to

connect to it run the following:

(gdb) target remote :1337

Remote debugging using :1337

0x00000116 in nrf52833_pac::{{impl}}::fmt (self=0xd472e165, f=0x3c195ff7) at /home/nix/.cargo/registry/src/github.com-1ecc6299db9ec823/nrf52833-pac-0.9.0/src/lib.rs:157

157 #[derive(Copy, Clone, Debug)]

NOTE The example in the repository for this chapter may change over time. Line numbers and other source details may thus be different from what is shown here and below.

If the program fails to halt after starting, and you end up somewhere deeper in the program like the following, then try running

monitor reset haltto reset. This is due to a bug inprobe-rs, see issue #27 for more details.(gdb) target remote :1337 Remote debugging using :1337 init::__cortex_m_rt_main () at mdbook/src/05-meet-your-software/examples/init.rs:19 19 asm::nop(); (gdb) monitor reset halt Resetting and halting target Target halted

Next what we want to do is get to the main function of our program. We will do this by first

setting a breakpoint there and then continuing program execution until we hit the breakpoint:

(gdb) break main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x104: file src/05-meet-your-software/examples/init.rs, line 9.

Note: automatically using hardware breakpoints for read-only addresses.

(gdb) continue

Continuing.

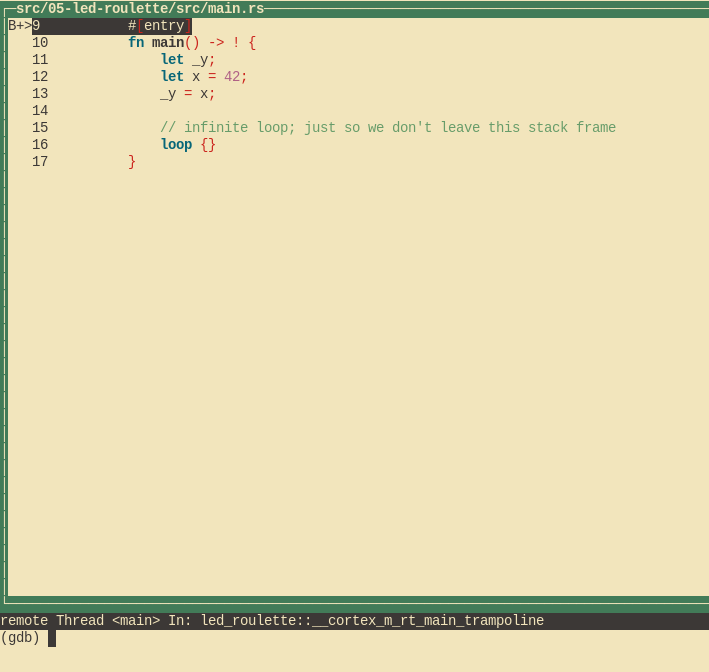

Breakpoint 1, init::__cortex_m_rt_main_trampoline () at src/05-meet-your-software/examples/init.rs:9

9 #[entry]

Breakpoints can be used to stop the normal flow of a program. The continue command will let the

program run freely until it reaches a breakpoint. In this case, until it reaches the main

function because there’s a breakpoint there.

Note that GDB output says “Breakpoint 1”. Remember that our processor can only use a limited amount

of these breakpoints, so it’s a good idea to pay attention to these messages. If you happen to run

out of breakpoints, you can list all the current ones with info break and delete desired ones with

delete <breakpoint-num>.

For a nicer debugging experience, we’ll be using GDB’s Text User Interface (TUI). To enter into that mode, on the GDB shell enter the following command:

(gdb) layout src

NOTE Apologies Windows users. The GDB shipped with the GNU Arm Embedded Toolchain doesn’t support this TUI mode

:-(.

GDB’s break command does works for more than just function names: it can also break at certain line numbers. If we want to break in line 13 we can simply do:

(gdb) break 13

Breakpoint 2 at 0x110: file src/05-meet-your-software/examples/init.rs, line 13.

(gdb) continue

Continuing.

Breakpoint 2, init::__cortex_m_rt_main () at src/05-meet-your-software/examples/init.rs:13

(gdb)

At any point you can leave the TUI mode using the following command:

(gdb) tui disable

We are now “on” the _y = x statement; that statement hasn’t been executed yet. This means that x

is initialized but _y could contain anything. Let’s inspect x using the print command:

(gdb) print x

$1 = 42

(gdb) print &x

$2 = (*mut i32) 0x20003fe8

(gdb)

As expected, x contains the value 42. The command print &x prints the address of the variable

x. The interesting bit here is that GDB output shows the type of the reference: *mut i32, a

pointer to a mutable i32 value.

If we want to continue the program execution line by line, we can do that using the next command.

Let’s proceed to the loop {} statement:

(gdb) next

16 loop {}

And _y should now be initialized.

(gdb) print _y

$5 = 42

Instead of printing the local variables one by one you can also use the info locals command:

(gdb) info locals

x = 42

_y = 42

(gdb)

If we use next again on top of the loop {} statement, we’ll get stuck because the program will

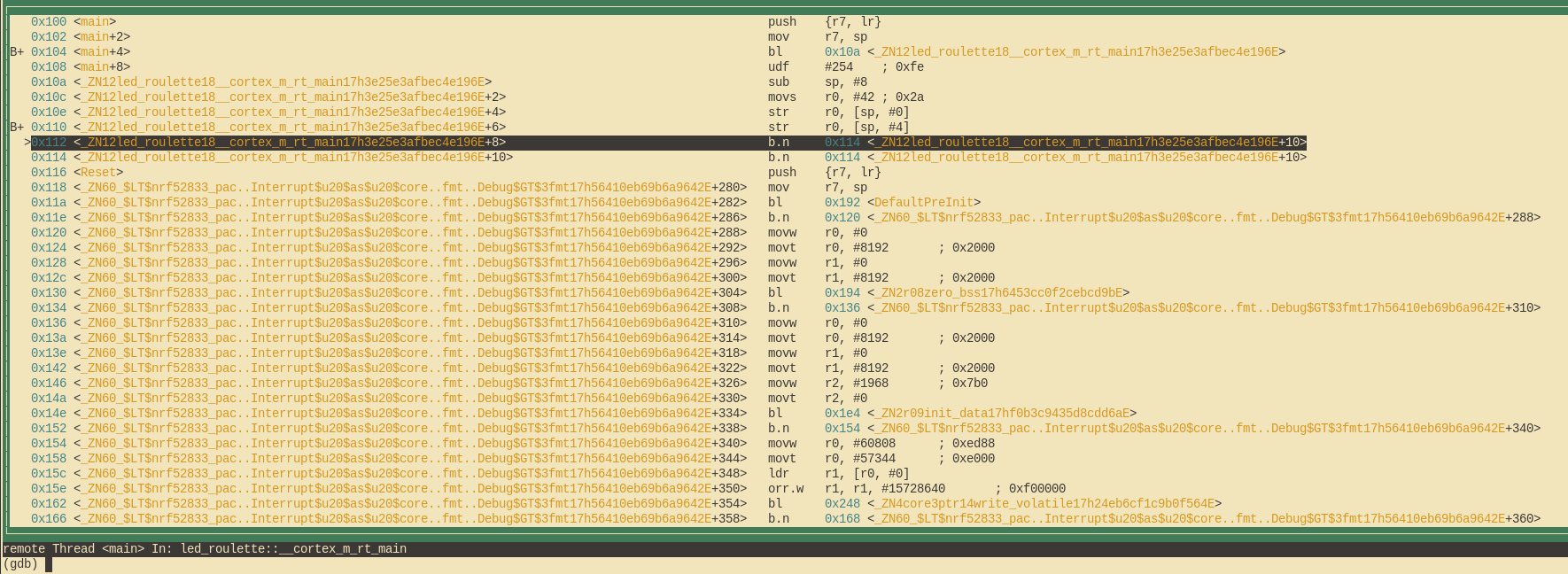

never pass that statement. Instead, we’ll switch to the disassemble view with the layout asm

command and advance one instruction at a time using stepi. You can always switch back into Rust

source code view later by issuing the layout src command again.

NOTE If you used the

nextorcontinuecommand by mistake and GDB got stuck, you can get unstuck by hittingCtrl+C.

(gdb) layout asm

If you are not using the TUI mode, you can use the disassemble /m command to disassemble the

program around the line you are currently at.

(gdb) disassemble /m

Dump of assembler code for function _ZN12init18__cortex_m_rt_main17h3e25e3afbec4e196E:

10 fn main() -> ! {

0x0000010a <+0>: sub sp, #8

0x0000010c <+2>: movs r0, #42 ; 0x2a

11 let _y;

12 let x = 42;

0x0000010e <+4>: str r0, [sp, #0]

13 _y = x;

0x00000110 <+6>: str r0, [sp, #4]

14

15 // infinite loop; just so we don't leave this stack frame

16 loop {}

=> 0x00000112 <+8>: b.n 0x114 <_ZN12init18__cortex_m_rt_main17h3e25e3afbec4e196E+10>

0x00000114 <+10>: b.n 0x114 <_ZN12init18__cortex_m_rt_main17h3e25e3afbec4e196E+10>

End of assembler dump.

See the fat arrow => on the left side? It shows the instruction the processor will execute next.

If not inside the TUI mode on each stepi command GDB will print the statement and the line number

of the instruction the processor will execute next.

(gdb) stepi

16 loop {}

(gdb) stepi

16 loop {}

One last trick before we move to something more interesting. Enter the following commands into GDB:

(gdb) monitor reset

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Breakpoint 1, init::__cortex_m_rt_main_trampoline () at src/05-meet-your-software/src/main.rs:9

9 #[entry]

(gdb)

We are now back at the beginning of main!

monitor reset will reset the microcontroller and stop it right at the program entry point.

The following continue command will let the program run freely until it reaches the main

function that has a breakpoint on it.

This combo is handy when you, by mistake, skipped over a part of the program that you were interested in inspecting. You can easily roll back the state of your program back to its very beginning.

The fine print: This

resetcommand doesn’t clear or touch RAM. That memory will retain its values from the previous run. That shouldn’t be a problem though, unless your program behavior depends on the value of uninitialized variables — but that’s the definition of Undefined Behavior (UB).

We are done with this debug session. You can end it with the quit command.

(gdb) quit

A debugging session is active.

Inferior 1 [Remote target] will be detached.

Quit anyway? (y or n) y

Detaching from program: $PWD/target/thumbv7em-none-eabihf/debug/meet-your-software, Remote target

Ending remote debugging.

[Inferior 1 (Remote target) detached]

NOTE If the default GDB CLI is not to your liking check out gdb-dashboard. It uses Python to turn the default GDB CLI into a dashboard that shows registers, the source view, the assembly view and other things.

If you want to learn more about what GDB can do, check out the section How to use GDB.

What’s next? The high level API I promised.

Light it up

We will finish this chapter by making one of the many LEDs on the MB2 light up. In order to get this

task done we will use one of the traits provided by embedded-hal, specifically the OutputPin

trait which allows us to turn a pin on or off.

The micro:bit LEDs

On the back of the micro:bit you can see a 5x5 square of LEDs, usually called an LED matrix. This matrix alignment is used so that instead of having to use 25 separate pins to drive every single one of the LEDs, we can just use 10 (5+5) pins in order to control which column and which row of our matrix lights up.

Right now we will use the microbit-v2 crate to manipulate the LEDs. In the next chapter we will

go in detail through all of the options available.

Actually lighting it up!

The code required to light up an LED in the matrix is actually quite simple but it requires a bit of

setup. First take a look at src/main.rs; then we can go through it step by step.

#![deny(unsafe_code)]

#![no_main]

#![no_std]

use cortex_m_rt::entry;

use embedded_hal::digital::OutputPin;

use microbit::board::Board;

use panic_halt as _;

#[entry]

fn main() -> ! {

let mut board = Board::take().unwrap();

board.display_pins.col1.set_low().unwrap();

board.display_pins.row1.set_high().unwrap();

loop {}

}The first few lines until the main function just do some basic imports and setup we mostly looked

at before. However, the main function looks pretty different to what we have seen up to now.

The first line is related to how most HALs written in Rust work internally. As discussed before they are built on top of PAC crates which own (in the Rust sense) all the peripherals of a chip. When we say

let mut board = Board::take().unwrap();

We take all of these peripherals from the PAC and bind them to a variable. In this specific case we are not only working with a HAL but with an entire BSP, so this also takes ownership of the Rust representation of the other chips on the board.

NOTE: If you are wondering why we have to call

unwrap()here, in theory it is possible fortake()to be called more than once. This would lead to the peripherals being represented by two separate variables and thus lots of possible confusing behaviour because two variables modify the same resource. In order to avoid this, PACs are implemented in a way that it would panic if you tried to take the peripherals twice.

(Again, if you are confused by all of this, the next chapter will go through it all again in greater detail.)

Now we can light the LED connected to row1, col1 up by setting the row1 pin to high

(i.e. switching it on). The reason we can leave col1 set to low is because of how the LED matrix

circuit works. Furthermore, embedded-hal is designed in a way that every operation on hardware can

possibly return an error, even just toggling a pin on or off. Since that is highly unlikely in our

case, we can just unwrap() the result.

Testing it

Testing our little program is quite simple. We run cargo embed

and let it flash just like before. Then open our GDB and

connect to the GDB stub.

$ gdb ../../../target/thumbv7em-none-eabihf/debug/meet-your-software

(gdb) target remote :1337

Remote debugging using :1337

cortex_m_rt::Reset () at /home/nix/.cargo/registry/src/github.com-1ecc6299db9ec823/cortex-m-rt-0.6.12/src/lib.rs:489

489 pub unsafe extern "C" fn Reset() -> ! {

(gdb)

We now let the program run via the GDB continue command:

one of the LEDs on the front of the micro:bit should light

up.

Hello World

In the last section, you wrote a sort of “Hello World” program. But for embedded programmers, the “real Hello World” is to blink an LED — any LED — on and off once per second. A program that does this is commonly known as a “blinky”.

Why blinky? Because this shows that you have enough control of the board you’re working with to perform this simple task. You can get a program loaded onto the machine and running, you can find and turn on the appropriate pin on the MCU, you can delay for a fixed amount of time. Once you have this much control, other tasks become much more straightforward.

In previous chapters, you found out several ways to load a program onto your MB2. Now it’s just a question of which pin you turn on and off, and how you delay between these actions.

Let’s start by finding out how to work with the needed pins. There’s a path you can follow for this if you know how to read electronic circuit “schematic” diagrams. You can find the MB2 schematic, find an LED on that schematic that you want to turn on and off, and find what GPIO pins on the nRF52833 are attached to that LED. (The MB2 is a bit unusual in this regard: usually an LED is attached to just one pin that turns it on or off. The LED “display” on the MB2 is hooked up in a more complicated way to allow turning on and off combinations of LEDs at once: a feature that we will be using shortly.)

We will work with the LED in the upper-left corner of the MB2 display. Tracing the ROW1 and COL1

wires this LED is connected to, we can see that they go to pins on the nRF52833 labeled

AC17/P0.21 and B11/AIN4/P0.28. Digging further through the documentation we find that

AC17 and B11 are the row and column indices of the physical pins (solder balls, really) on the

bottom of the chip — useless to us. AIN4 just means that this pin can act as an “Analog Input”,

which is also currently useless to us. (It will come into play later.)

This leaves P0.21 and P0.28. These labels correspond to bits in the memory of the nRF52833 that

can be turned on and off to get the LED to light up. Because electronics reasons, if pin P0.21 is

turned on (thus outputting 3.3V) and pin P0.28 is turned off (thus accepting voltage) the LED will

light up.

But what do we do in software to cause this to occur? We will work at the level of the

nrf52833-hal crate. The Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL) is a chunk of software designed to make a

particular microcontroller easier to work with. As can be seen from the name, we have one for the

microcontroller on the MB2. It happens to contain everything needed to turn our target LED on.

Take a look at examples/light-up.rs in this chapter’s directory, and then try running it.

You could use something fancy like before, but we have it set up so that

cargo run --example light-up

will load and run your program. That one LED should now be brightly lit!

#![no_main]

#![no_std]

use cortex_m_rt::entry;

use nrf52833_hal::{gpio, pac};

use panic_halt as _;

#[entry]

fn main() -> ! {

let peripherals = pac::Peripherals::take().unwrap();

let p0 = gpio::p0::Parts::new(peripherals.P0);

let _row1 = p0.p0_21.into_push_pull_output(gpio::Level::High);

let _col1 = p0.p0_28.into_push_pull_output(gpio::Level::Low);

#[allow(clippy::empty_loop)]

loop {}

}Note that we access the Peripheral Access Crate (PAC) for this chip through our HAL crate. There’s a complicated dance needed to get access to our pins. Finally, since we can just initialize the pins to the right levels, we don’t need to set them. Wiggling the pins is a topic for the next section.

Toggle it

Let’s turn the LED on and off repeatedly. That’s how you make it blink, right?

In examples/fast-blink.rs you’ll find the next iteration of our blinky. I’ve decided to make it

blink the next LED over, while leaving the original LED on. That is an easy change.

#![no_main]

#![no_std]

use cortex_m_rt::entry;

use embedded_hal::digital::OutputPin;

use nrf52833_hal::{gpio, pac};

use panic_halt as _;

#[entry]

fn main() -> ! {

let peripherals = pac::Peripherals::take().unwrap();

let p0 = gpio::p0::Parts::new(peripherals.P0);

let _row1 = p0.p0_21.into_push_pull_output(gpio::Level::High);

let mut row2 = p0.p0_22.into_push_pull_output(gpio::Level::Low);

let _col1 = p0.p0_28.into_push_pull_output(gpio::Level::Low);

loop {

row2.set_high().unwrap();

row2.set_low().unwrap();

}

}The embedded-hal crate is being used here to provide the Rust traits needed to set and unset the

LED. This means that this part of the code is portable to any Rust HAL that implements the

embedded-hal traits as ours does.

But wait: neither LED is blinking! The second one is slightly dimmer than the first one, but they are both solidly on… or are they? Out of the box, the MB2 executes 64 million instructions per second. Let’s assume it takes a few dozen instructions under the hood to turn the LED on or off. (Maybe possibly that many compiled in debug mode, though way less in release mode. Though the pins take a while to change state. I don’t know.) Anyhow, that second LED is actually turning on and off hundreds of thousands of times — perhaps millions of times — every second. Your eye just can’t keep up.

We’ll need to wait a while between toggles. Turns out waiting is the hardest part.

Spin wait

To blink the LED, we need to wait about a half-second between each change. How do we do that?

Well, here’s the dumb way. It’s not good, but it’s a start. Take a look at examples/spin-wait.rs.

#![no_main]

#![no_std]

use cortex_m::asm::nop;

use cortex_m_rt::entry;

use embedded_hal::digital::OutputPin;

use nrf52833_hal::{gpio, pac};

use panic_halt as _;

fn wait() {

for _ in 0..4_000_000 {

nop();

}

}

#[entry]

fn main() -> ! {

let peripherals = pac::Peripherals::take().unwrap();

let p0 = gpio::p0::Parts::new(peripherals.P0);

let mut row1 = p0.p0_21.into_push_pull_output(gpio::Level::High);

let _col1 = p0.p0_28.into_push_pull_output(gpio::Level::Low);

loop {

wait();

row1.set_high().unwrap();

wait();

row1.set_low().unwrap();

}

}Run this with cargo run --release --example spin-wait — the --release is really important here — and

you should see the LED on your MB2 flash on and off about once per second.

Things you might be wondering:

-

What are those

_characters in that number? Rust allows these in numbers and ignores them. It’s really convenient to make big numbers more readable. Here we are using them as commas (or whatever the separator is for groups of three digits in your country). -

If the nRF52833 is running at 64MHz, why is the wait loop iterating only 4M times? Shouldn’t it be 32M? The wait loop executes several instructions each time through: the

nop(see next section), some bookkeeping, and a branch back to the start of the loop. The code generated is roughly this for the firstwait()call.LBB1_4: adds r3, #1 nop cmp r3, r2 bne .LBB1_4and this for the second

.LBB1_6: subs r3, #1 nop bne .LBB1_6This is only three or four instructions, but the backward branch may cost an extra bit. Notice that these are not the same: the compiler chooses to emit different instructions for the first and second wait loops. See “it varies depending” below.

Still, we’re executing about 4 instructions per loop iteration. This means that on our 64MHz CPU a half-second spin should take 64M/2/4 = 8M iterations to complete. So something is slowing us down by a factor of 2. What? I dunno. This whole thing is terrible.

-

Why is

--releaseso all-important? Try without it. Notice that the LED is still flashing on and off, but with a period of many seconds. The wait loop is now unoptimized and is taking many instructions each time through. -

What is that

nop()call and why is it there? We shall answer this in the next section. -

Why do you refer to this as “the dumb way”?

-

It isn’t precise. Trying to tune that loop to reliably hit exactly 0.5 seconds is… not really a thing.

-

It varies depending. Different CPU? Different compilation flags? Different anything really? Now the timing has changed.

-

It sucks power. The CPU is running instructions as fast as it can, just to stay in place. If there’s nothing else for it to do, it should quietly sleep until it is needed again. This doesn’t matter much if you have USB power. But if you hook up your MB2 using the battery pack you’ll really feel this.

-

In the next section, we’ll discuss nop(). After that, we’ll talk more about the other things about

our blinky that need improving.

For such a simple program, this is a pretty complicated program. That’s why we start with blinky.

NOP

You might wonder what that nop() call is doing in the wait() loop in src/bin/spin-wait.rs.

The answer is that it literally does nothing. The nop() function causes the compiler to put a

NOP Arm machine instruction at that point in the program. NOP is a special instruction that

causes the CPU to skip it. To ignore it. To literally do No OPeration with it (hence the name).

So get rid of that line and recompile the program. Don’t forget --release mode. Then run it.

We’re back to a slightly darker solid LED again. With no loop body, the compiler’s optimizer decided

that wait() function wasn’t doing anything. So it just removed it for you at compile time. Thanks

optimizer. You have made my wait loop infinitely fast.

How does nop() do its job? Well, if you look at the implementation of nop() you will find

(after a bunch of digging around) that it is implemented like this:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

asm!("nop", options(nomem, nostack, preserves_flags));

}The nop() function is “inlined”, so when you “call” it an actual Arm NOP assembly instruction is

inserted into your program’s code at that point. Because details, this NOP will not be removed or

moved around by the compiler: it will stay right there where you put it.

The ability to insert assembly code into your program where needed is sometimes quite important in

embedded programming. Sometime a CPU will have instructions the compiler doesn’t know about, but

that you still need in order to use the CPU effectively. Rust’s asm!() directive gives you a way

to do that.

Our spin-wait is still terrible. Let’s talk about doing better.

Timers

One of the big advantages of a “bare-metal” embedded system is that you control everything that happens on your machine. This allows you to have really precise control of time: nothing will slow you down unless you let it.

However, we’ve seen that if we really want to get time right, we probably need help. Embedded MCUs like the nRF52833 all provide this kind of help in the form of “timers”. A timer is a peripheral that, as its name implies, acts like a little clock that keeps very precise track of time.

The nRF52833 contains four timers. If you look at the documentation for the chip, you’ll find that

they are pretty complicated to set up and use. Luckily, the HAL provides a wrapper around timers

that makes common uses easy. The most common use of a timer is to delay for a precise amount of

time: just what our wait() function of the previous sections was trying to do.

Take a look at examples/timer-blinky.rs. This code sets up a timer and uses it to delay for 500ms

(0.5s) between each toggle.

#![no_main]

#![no_std]

use cortex_m_rt::entry;

use embedded_hal::{delay::DelayNs, digital::OutputPin};

use nrf52833_hal::{gpio, pac, timer};

use panic_halt as _;

#[entry]

fn main() -> ! {

let peripherals = pac::Peripherals::take().unwrap();

let p0 = gpio::p0::Parts::new(peripherals.P0);

let mut row1 = p0.p0_21.into_push_pull_output(gpio::Level::High);

let _col1 = p0.p0_28.into_push_pull_output(gpio::Level::Low);

let mut timer0 = timer::Timer::new(peripherals.TIMER0);

loop {

timer0.delay_ms(500);

row1.set_high().unwrap();

timer0.delay_ms(500);

row1.set_low().unwrap();

}

}Run this code with cargo run --release --example timer-blinky and time it with a stopwatch. You’ll

find that it is exactly one second for each on-off cycle.

Things you might notice:

-

We need to use the

embedded_hal::Delaytrait to get thedelay_ms()method we’re using. -

As before, we dig the peripheral out of the PAC peripherals struct and give it to the HAL.

Now we have a production-quality blinky. Let’s talk a bit about the implications of all this.

Portability

(This section is optional. Feel free to skip to the next section, where we clean our code up a bit and call it a day.)

You may wonder whether all this fancy ecosystem is worth its weight. The setup for our blinky is pretty fancy, and uses a lot of Rust crates and features for such a simple job.

One cool advantage, though, is that our code becomes really portable. On a different board, the setup may be different, but the actual blinky loop is identical!

Let’s take a look at a blinky for the Sipeed Longan Nano. This is a little $5 board that, like the MB2, is an embedded board with an MCU. Otherwise, it is completely different: different processor (the GD32VF103, with a RISC-V instruction set entirely unlike the Arm instruction set we’re using), different peripherals, different board. But it has an LED attached to a GPIO pin, so we can blinky it.

#![no_std]

#![no_main]

use panic_halt as _;

use riscv_rt::entry;

use gd32vf103xx_hal::{pac, prelude::*, delay::McycleDelay};

use embedded_hal::{blocking::delay::DelayMs, digital::v2::OutputPin};

#[entry]

fn main() -> ! {

let dp = pac::Peripherals::take().unwrap();

let mut rcu = dp.RCU.configure().ext_hf_clock(8.mhz()).sysclk(108.mhz()).freeze();

let gpioc = dp.GPIOC.split(&mut rcu);

let mut led = gpioc.pc13.into_push_pull_output();

let mut delay = McycleDelay::new(&rcu.clocks);

loop {

delay.delay_ms(500);

led.set_high().unwrap();

delay.delay_ms(500);

led.set_low().unwrap();

}

}The differences in setup here are partly because different hardware, and partly because this code

uses an older HAL crate that hasn’t yet been updated for embedded-hal 1.0. Yet the main loop is

identical as advertised, and the rest of the code is pretty recognizable. Because of the portability

provided by Rust’s easy cross-compilation and the embedded Rust ecosystem, blinky is just blinky.

You can find a complete working nanoblinky example on GitHub, if you want to see all the details or even get your own board and try it yourself.

Board support crate

Working directly with the PAC and HAL is pretty neat. Most Arm MCUs and many other MCUs that Rust can compile for have a PAC crate. If you are working with one that does not, writing a PAC crate can be tedious but is pretty straightforward. Many MCUs that have a PAC crate also have a HAL crate — again, it’s mostly just tedious work to build one if it is absent. Code written at the PAC and HAL level gives access to the fine details of the MCU.

As we have seen, though, it becomes pretty annoying to keep track of just what is going on at the interface between our nRF52833 and the rest of our MB2. We have had to read schematics and whatnot to see how to use our off-board hardware.

A “board support crate” — known in the non-Rust embedded community as a Board Support Package (BSP)

— is a crate built on top of the HAL and PAC for a board to abstract away the details and provide

conveniences. The board support crate we have been working with is the microbit-v2 crate.

Let’s use microbit-v2 to get a final, cleaned up blinky (src/main.rs).

#![no_main]

#![no_std]

use cortex_m_rt::entry;

use embedded_hal::{delay::DelayNs, digital::OutputPin};

use microbit::hal::{gpio, timer};

use panic_halt as _;

#[entry]

fn main() -> ! {

let board = microbit::Board::take().unwrap();

let mut row1 = board.display_pins.row1.into_push_pull_output(gpio::Level::High);

let _col1 = board.display_pins.col1.into_push_pull_output(gpio::Level::Low);

let mut timer0 = timer::Timer::new(board.TIMER0);

loop {

timer0.delay_ms(500);

row1.set_high().unwrap();

timer0.delay_ms(500);

row1.set_low().unwrap();

}

}In this case, we haven’t changed much. Our board support crate has hidden the PAC (for now). More importantly, it has done so by letting us just use reasonable names for the row and column GPIO pins for the LED.

The microbit-v2 crate provides even fancier support for those “display” LEDs. We will see this

support used soon to do things more fun than blinky.

LED roulette

Alright, let’s build a “real” application. The goal is to get to this display of spinning lights:

Since working with the LED pins separately is quite annoying (especially if you have to use

basically all of them like here) you can use the microbit-v2 BSP crate, discussed previously, to

work with the MB2’s LED “display”. It works like this (examples/light-it-all.rs):

#![no_main]

#![no_std]

use cortex_m_rt::entry;

use embedded_hal::delay::DelayNs;

use microbit::{board::Board, display::blocking::Display, hal::Timer};

use panic_rtt_target as _;

use rtt_target::rtt_init_print;

#[entry]

fn main() -> ! {

rtt_init_print!();

let board = Board::take().unwrap();

let mut timer = Timer::new(board.TIMER0);

let mut display = Display::new(board.display_pins);

let light_it_all = [

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

];

loop {

// Show light_it_all for 1000ms

display.show(&mut timer, light_it_all, 1000);

// clear the display again

display.clear();

timer.delay_ms(1000_u32);

}

}The Rust array light_it_all shown in the example contains 1 where the LED is on and 0 where it is

off. The call to show() takes a timer for the BSP display code to use for delaying, a copy of

the array, and a length of time in milliseconds to show this display before returning.

The challenge

You are now well armed to face our challenge! Again, your application should look like this:

If you can’t exactly see what’s happening here it is in a much slower version:

If you need a hint, templates/solution.rs provides a mostly-filled-out chunk of code to finish. I

would suggest you try it on your own first, though: it should be doable by now…

Got it?

My solution

What solution did you come up with?

Here’s mine. It’s probably one of the simplest (but of course not most beautiful) ways to generate the required matrix:

#![deny(unsafe_code)]

#![no_main]

#![no_std]

use cortex_m_rt::entry;

use microbit::{board::Board, display::blocking::Display, hal::Timer};

use panic_rtt_target as _;

use rtt_target::rtt_init_print;

#[rustfmt::skip]

const PIXELS: [(usize, usize); 16] = [

(0, 0),

(0, 1),

(0, 2),

(0, 3),

(0, 4),

(1, 4),

(2, 4),

(3, 4),

(4, 4),

(4, 3),

(4, 2),

(4, 1),

(4, 0),

(3, 0),

(2, 0),

(1, 0),

];

#[entry]

fn main() -> ! {

rtt_init_print!();

let board = Board::take().unwrap();

let mut timer = Timer::new(board.TIMER0);

let mut display = Display::new(board.display_pins);

#[rustfmt::skip]

let mut leds = [

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

];

let mut last_led = (0, 0);

loop {

for current_led in PIXELS {

leds[last_led.0][last_led.1] = 0;

leds[current_led.0][current_led.1] = 1;

display.show(&mut timer, leds, 200);

last_led = current_led;

}

}

}One more thing! Check that your solution also works when compiled in “release” mode:

$ cargo embed --release

If you want to debug your “release” mode binary you’ll have to use a different GDB command:

$ gdb ../../../target/thumbv7em-none-eabihf/release/led-roulette

The Rust compiler modifies the machine instructions generated in a release build (sometimes by a lot) in order to try to make the code faster or smaller. Unfortunately, GDB has a hard time figuring out what is going on after this. As a result, debugging release builds with GDB can be difficult.

Binary size is something we should always keep an eye on! How big is your solution? You can check

that using the size command on the release binary:

$ cargo size --release -- -A

Finished release [optimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.02s

led-roulette :

section size addr

.vector_table 256 0x0

.text 6332 0x100

.rodata 648 0x19bc

.data 0 0x20000000

.bss 1076 0x20000000

.uninit 0 0x20000434

.debug_loc 9036 0x0

.debug_abbrev 2754 0x0

.debug_info 96460 0x0

.debug_aranges 1120 0x0

.debug_ranges 11520 0x0

.debug_str 71325 0x0

.debug_pubnames 32316 0x0

.debug_pubtypes 29294 0x0

.Arm.attributes 58 0x0

.debug_frame 2108 0x0

.debug_line 19303 0x0

.comment 109 0x0

Total 283715

Your numbers may differ somewhat depending on how your code is built: this is OK.

Know how to read this output? The text section contains the program instructions. The rodata

section contains read-only data stored with the program instructions. The data and bss sections

contain variables statically allocated in RAM (static variables). If you remember the

specification of the microcontroller on your micro:bit, you should notice that its flash memory is

less than double the size of this extremely simple binary: can this be right? As we can see from

the size statistics most of the binary is actually made up of debugging related sections. However,

those are not flashed to the microcontroller at any time — after all they aren’t relevant for the

execution.

Inputs and Polling

In earlier chapters, we’ve explored GPIO pins primarily as outputs—driving LEDs on and off. However, GPIO pins can also be configured as inputs, allowing your program to read signals from the physical world, like button presses or switch toggles. In this chapter, we’ll learn how to read these input signals and do something useful with them.

Reading Button State

The micro:bit v2 has two physical buttons, Button A and Button B, connected to GPIO pins configured as inputs. Specifically, Button A is connected to pin P0.14, and Button B to pin P0.23. (You can verify this from the official pinmap table.)

Reading the state of a GPIO input involves checking whether the voltage level at the pin is high (3.3V, logic level 1) or low (0V, logic level 0). Each button on the micro:bit is connected to a pin. When the button is not pressed, that pin is held high; when the button is pressed, the pin is held low.

Let’s now apply this knowledge to reading the state of Button A by checking if the button is “low” (pressed).

#![no_main]

#![no_std]

use cortex_m_rt::entry;

use embedded_hal::digital::InputPin;

use microbit::Board;

use panic_rtt_target as _;

use rtt_target::{rprintln, rtt_init_print};

#[entry]

fn main() -> ! {

rtt_init_print!();

let board = Board::take().unwrap();